Stephen M. Bainbridge is William D. Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law and serves as the WLF Legal Pulse’s Featured Expert Contributor, Corporate Governance/Securities Law.

Stephen M. Bainbridge is William D. Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, UCLA School of Law and serves as the WLF Legal Pulse’s Featured Expert Contributor, Corporate Governance/Securities Law.

In Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi, (Del. Mar. 18, 2020), the Delaware Supreme validated forum selection clauses in the certificates of incorporation of Blue Apron Holdings, Inc., Stitch Fix, Inc., and Roku, Inc., all of which required that claims against the companies brought under the Securities Act of 1933 be brought in federal courts. In 2015, the Delaware legislature had added § 115 to the Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL) to validate forum selection clauses that “require … that any or all internal corporate claims shall be brought solely and exclusively in any or all of the courts in this State.” Although § 115 on its face neither validated nor banned federal forum selection clauses, many corporations have adopted such clauses.

Section 115 arose out of concern with a substantial increase in the volume of multijurisdictional litigation against Delaware firms involving corporate law issues. Traditionally, most corporate law cases involving a Delaware corporation were tried in the Delaware Chancery Court. Starting around 2000, however, there were two dramatic changes in corporate litigation. First, there was a substantial increase in the number of cases being brought, especially with respect to mergers and acquisitions. Indeed, lawsuits challenging some aspect of an acquisition became near universal. Second, it became common for multiple lawsuits to be filed in multiple jurisdictions against each deal.

In response, Delaware corporations began adding forum selection clauses to their certificates of incorporation. In 2010, dicta in an opinion by Vice Chancellor Laster suggested that the Delaware courts would look favorably upon such clauses: “if boards of directors and stockholders believe that a particular forum would provide an efficient and value-promoting locus for dispute resolution, then corporations are free to respond with charter provisions selecting an exclusive forum for intra-entity disputes.” In re Revlon, Inc. Shareholders Litig., 990 A.2d 940, 960 (Del. Ch. 2010). Laster’s prediction was confirmed in Boilermakers Local 154 Retirement Fund v. Chevron Corp., 73 A.3d 934 (Del. Ch. 2013), in which then-Chancellor Leo Strone upheld bylaws “providing that litigation relating to [the company’s] internal affairs should be conducted in Delaware.” Id. at 937. Section 115 subsequently codified that holding.

As noted, Section 115 did not address the question of whether a corporation could adopt a similar provision addressing claims arising under federal law. The precedent it created, however, encouraged firms to respond to the growing number of lawsuits being brought under federal law. Plaintiffs’ counsel long had looked to evade the restrictions put on federal securities lawsuits by the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act by bringing federal claims in state court. This trend got a boost from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Ret. Fund, 138 S. Ct. 1061 (2018), which held that Securities Act claims could be brought in state court and that such claims could not be removed to federal court.

Because many companies believed that state courts were more pro-plaintiff than federal courts and because they wished to avoid multiple suits being brought in multiple states, they began adopting federal forum selection clauses such as those instituted by Blue Apron, Roku, and Stitch Fix. The version adopted by both Roku and Stitch Fix is typical:

Unless the Company consents in writing to the selection of an alternative forum, the federal district courts of the United States of America shall be the exclusive forum for the resolution of any complaint asserting a cause of action arising under the Securities Act of 1933. Any person or entity purchasing or otherwise acquiring any interest in any security of [the Company] shall be deemed to have notice of and consented to [this provision].

When an investor sued in Chancery Court seeking a declaratory judgment that these federal forum selection clauses were illegal under Delaware law, VC Laster agreed. He first held that the analysis used in Boilermakers to determine the validity of forum selection bylaws also applied to forum selection provisions in certificates of incorporation. Laster next interpreted Boilermakers as drawing a sharp line between litigation involving internal corporate matters—such as corporate law claims against a firm’s directors and officers—and litigation involving external matters—such as “a bylaw that purported to bind a plaintiff, even a stockholder plaintiff, who sought to bring a tort claim against the company based on a personal injury she suffered that occurred on the company’s premises.” Boilermakers, 73 A.3d at 952. Only the former would be proper.

Finally, Laster concluded that claims arising under federal securities law fell into the prohibited external category:

For purposes of the analysis in Boilermakers, a 1933 Act claim resembles a tort or contract claim brought by a third-party plaintiff who was not a stockholder at the time the claim arose. At best for the defendants, a 1933 Act claim resembles a tort or contract claim brought by a plaintiff who happens also to be a stockholder, but under circumstances where stockholder status is incidental to the claim. A 1933 Act claim is an external claim that falls outside the scope of the corporate contract.

Sciabacucchi v. Salzberg, 2018 WL 6719718, at *18 (Del. Ch. Dec. 19, 2018), rev’d, 2020 WL 1280785 (Del. Mar. 18, 2020).

In reversing, the Delaware Supreme Court began with the text of DGCL § 102(b)(1), which addresses provisions that may be included in a certificate of incorporation and, in pertinent part, authorizes:

[1] Any provision for the management of the business and for the conduct of the affairs of the corporation, and [2] any provision creating, defining, limiting and regulating the powers of the corporation, the directors, and the stockholders, or any class of the stockholders …. (Enumeration supplied.)

The Court then concluded that a federal forum selection clause was authorized under either of the pertinent clauses of § 102(b)(1):

The drafting, reviewing, and filing of registration statements by a corporation and its directors is an important aspect of a corporation’s management of its business and affairs and of its relationship with its stockholders. This Court has viewed the overlap of federal and state law in the disclosure area as “historic,” “compatible,” and “complimentary.” Accordingly, a bylaw that seeks to regulate the forum in which such “intra-corporate” litigation can occur is a provision that addresses the “management of the business” and the “conduct of the affairs of the corporation,” and is, thus, facially valid under Section 102(b)(1).

Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi, 2020 WL 1280785, at *4 (Del. Mar. 18, 2020).

The Court buttressed that fiat with several additional arguments. First, it cited precedents holding that § 102(b)(1) is broadly enabling and thus only invalidates provisions forbidden by well-settled public policies. No such policies were implicated by the clauses in question. To the contrary, the Court had earlier in its opinion reasoned that state policy argued in favor of the clauses. It noted the rapid recent growth of Securities Act claims arising out of a single transaction being brought in multiple state courts. The Court asserted that the “costs and inefficiencies” of multijurisdictional litigation “are obvious.” Id. at *5. A federal forum selection clause reduced those costs by sending such cases to “to federal courts [where] coordination and consolidation are possible.” Id.

Second, noting that amendments to the certificates of incorporation require shareholder approval, the Court invoked Delaware precedents holding that “stockholder-approved charter amendments are given great respect.” Id. at *6. Relatedly, the Court reaffirmed that the DGCL in general and § 102(b) in particular are enabling and “allow[] immense freedom for businesses to adopt the most appropriate terms for the organization, finance and governance of their enterprise.” Id.

In addition to several other statutory arguments, the Court expressly rejected Laster’s narrow interpretation of corporate internal affairs. In doing so, the Court distinguished the sort of external matters identified by Boilermakers from the claims covered by the federal forum selection clauses, explaining that with those “types of claims, no Board action is present as it necessarily is in Section 11 claims, and those claims are unrelated to the corporation-stockholder relationship.” Id. at *12. In addition, the Court declined to embrace a sharp distinction between internal and external matters, observing that various matters fall “on a continuum” between those polar extremes. Id. at *13.

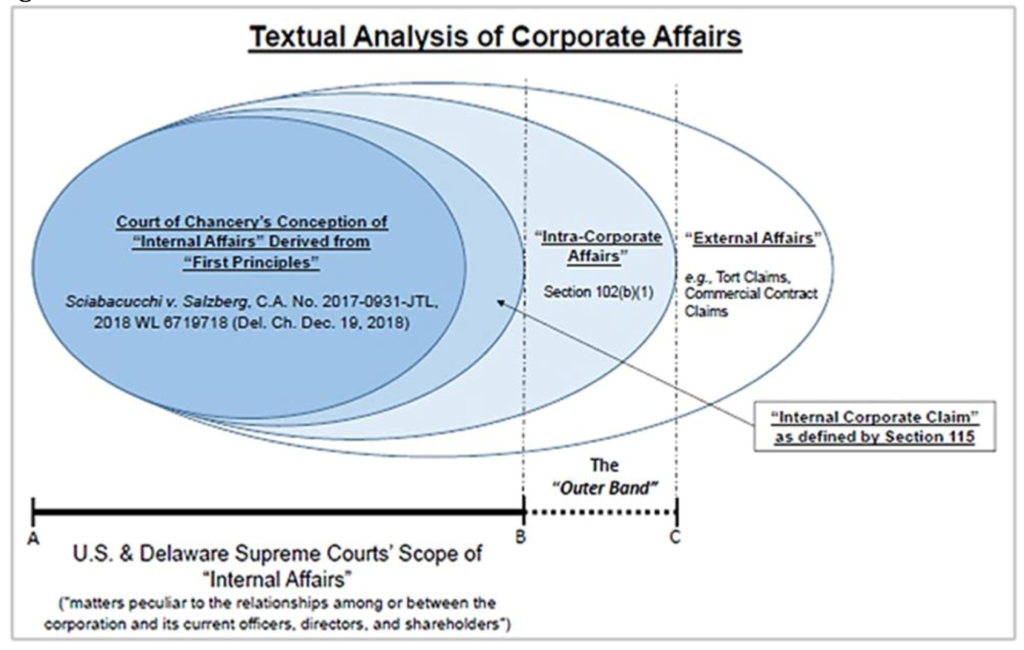

To illustrate its point, the Court offered the following diagram:

The court went on to explain that:

… there is an area outside of the “internal affairs” boundary but within the Section 102(b)(1) boundary (between points B and C on Figure 1), which, for convenience, we refer to as Section 102(b)(1)’s “Outer Band.” It is well-established that matters more traditionally defined as “internal affairs” or “internal corporate claims” are clearly within the protective boundaries (from points A to B) of Edgar, McDermott, and their progeny, where only one State has the authority to regulate a corporation’s internal affairs—the state of incorporation. There are matters that are not “internal affairs,” but are, nevertheless, “internal” or “intra-corporate” and still within the scope of Section 102(b)(1) and the “Outer Band,” represented in Figure 1 between points B to C. [Federal-forum provisions] FFPs are in this Outer Band, and are facially valid under Delaware law because they are within the statutory scope of Section 102(b)(1), as explained above.

In the wake of this decision, two questions present themselves. First, as the Court itself noted, there is a “’down the road’ question of whether they will be respected and enforced by our sister states.” Id. at *20.

… we recognize that it is a powerful concern that has infused much of the briefing here. The fear expressed in some of the briefing is that our sister states might react negatively to what could be viewed as an out-of-our-lane power grab. Some say that this perception, in turn, could invite greater scrutiny of even the well-established and respected “internal affairs” territory. Or it could invite a move towards federalization of our corporate law. These are legitimate concerns. Delaware historically has, and should continue to be, vigilant about not stepping on the toes of our sister states or the federal government.

But there are persuasive arguments that could be made to our sister states that a provision in a Delaware corporation’s certificate of incorporation requiring Section 11 claims to be brought in a federal court does not offend principles of horizontal sovereignty—just as it does not offend federal policy.

Id.

Second, what limits are there, if any, on the ability of corporations to adopt charter or bylaw provisions limiting shareholder rights? Widener University corporate law professor Lawrence Hamermesh has reportedly suggests that “fee-shifting provisions, class action waivers, or mandatory arbitration clauses” may now be valid. In contrast, prominent Delaware practitioner Francis Pileggi notes a footnote in the opinion suggesting that ““just because we’ve upheld the federal forum selection clause doesn’t mean that the floodgates are going to be open to allow arbitration provisions”:

Much of the opposition to FFPs seems to be based upon a concern that if upheld, the “next move” might be forum provisions that require arbitration of internal corporate claims. Such provisions, at least from our state law perspective, would violate Section 115 which provides that, “no provision of the certificate of incorporation or the bylaws may prohibit bringing such claims in the courts of this state.” 8 Del. C. § 115; see Del. S.B. 75 syn. (“Section 115 does not address the validity of a provision of the certificate of incorporation or bylaws that selects a forum other than the Delaware courts as an additional forum in which internal corporate claims may be brought, but it invalidates such a provision selecting the courts in a different State, or an arbitral forum, if it would preclude litigating such claims in the Delaware courts.” (emphasis added)).

Id. at *23 n.169. Note, however, that the footnote only addresses mandatory arbitration of state law-based claims. It does not speak to the question of whether a charter might mandate arbitration of federal securities law claims. Likewise, the Court’s diagram itself suggests that there are a range of shareholder claims as to which § 115 would not ban fee shifting bylaws.