Cross-posted at WLF’s Forbes.com contributor page

When a litigant files a certiorari petition in the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking review of a lower court decision, the opposing party has 30 days to file a response. The Supreme Court Clerk’s office can and does grant extensions of time to file a response when counsel for the opposing party sets out “specific reasons why an extension of time is justified.” But one should reasonably expect complete candor from attorneys, particularly federal government attorneys, when requesting such extensions. Events this week call into question whether the United States is being completely candid in explaining its extension requests.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit last May handed the federal government a major victory when it largely rejected First Amendment challenges to the new federal law that strictly regulates the labeling of tobacco products. The tobacco industry filed a Supreme Court certiorari petition in October, and the federal government’s brief in response to the petition was initially due on November 26, 2012. Since then, the Solicitor General’s Office has sought and received three successive extensions of time to respond, first to December 26, then to February 1, and then (in response to a request submitted just this week) to March 8. On all three occasions, the “specific reason” proffered for seeking an extension was that the government attorney assigned to the case was busy attending to other legal matters.

I have no inside knowledge regarding the workloads of government attorneys, but the too-busy-on-other-matters explanation is highly suspect in this instance. While the federal government routinely obtains one 30-day extension of filing deadlines in its Supreme Court cases and not infrequently obtains a second, the 98-day extension in this case is very unusual, even by federal government standards. Given the importance of the issues raised by the Sixth Circuit petition, entitled American Snuff Co. v. United States, and the Solicitor General’s ability to handle briefing in other cases, it does not seem plausible that his office could not have met the February 1 filing deadline.

A more plausible explanation arises from the fact that the Sixth Circuit’s decision directly conflicts with a recent decision from the D.C. Circuit, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA. The D.C. Circuit invoked the First Amendment to strike down the new health warnings mandated by FDA for all cigarette packaging. The federal government’s deadline for seeking Supreme Court review of that decision (unless it seeks and obtains an extension of time) is March 5, a date that very conveniently falls three days before the deadline for filing its response to the Sixth Circuit petition. It is undoubtedly in the federal government’s interest to have the Supreme Court consider the two certiorari petitions at the same time. Obtaining the additional extension of time for its response to the Sixth Circuit petition causes the briefing schedules in the two cases to coincide rather nicely, from the government’s perspective.

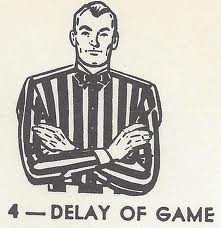

The loser in all of this is candor in Court filings. A government claim that it needs an extension of time because its attorneys are overworked does not qualify under Court Rule 30.4 as a “specific reason why an extension of time is justified” if it is not, in fact, the reason why an extension is sought. Assuming that the federal government’s goal is to ensure that the two petitions are considered together, it would have been far preferable had the Solicitor General filed a response to the Sixth Circuit petition this week and to have included therein a request that the Court hold its consideration of the petition until the federal government has an opportunity to file its anticipated petition from the D.C. Circuit decision.